The flood control plan is designed to control the "project flood." It is a flood larger than the record flood of 1927. At Cairo, the project flood is estimated at 2,360,000 cubic feet per second (cfs). The project flood is 11 percent greater than the flood of 1927 at the mouth of the Arkansas River and 29 percent greater at the latitude of Red River Landing, amounting to 3,030,000 cfs at that location, about 60 miles below Natchez.

Description of Plan

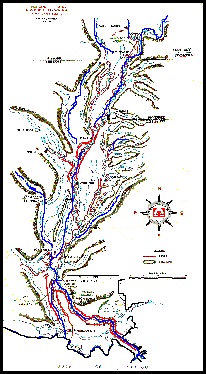

The four major elements of the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project are: levees for containing flood flows; floodways for the passage of excess flows past critical reaches of the Mississippi; channel improvement and stabilization for stabilizing the channel in order to provide an efficient navigation alignment, increase the flood-carrying capacity of the river, and for protection of the levees system; and tributary basin improvements for major drainage and for flood control, such as dams and reservoirs, pumping plants, auxillary channels, and the like.

Main Stem Levees

The Mississippi River levees are designed to protect the alluvial valley against the project flood by confining flow to the leveed channel, except where it enters the natural blackwater areas or is diverted purposely into the floodway areas.

The main stem levee system, comprised of levees, floodwalls, and various control structures, is 2,203 miles long. Some 1,607 miles lie along the Mississippi River itself and 596 miles lie along the south banks of the Arkansas and Red rivers and in the Atchafalaya Basin.

The levees are constructed by the federal government and are maintained by local interests, except for government assistance as necessary during major floods. Periodic inspections of maintenance are made by personnel from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and from local levee and drainage districts as it is essential that the levees be maintained in good condition for their proper functioning in the flood control plan.

Floodways

Cairo to New Madrid, Mo., the east bank bluffs and the levee as originally built on the west bank left only a narrow channel through which the river could flow at flood stage. To protect communities along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and to reduce the flood heights to which the controlling levees on the Missouri side would otherwise be subjected, the project provides for a setback levee about 5 miles west of the riverfront levee through this reach. The strip between this setback levee and the levee adjacent to the river forms what is known as the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway, operated only at extremely high stages. Water enters the floodway through lower levee sections or "fuse plugs" in the old front levee below Cairo and reenters the main river just above New Madrid. The floodway was operated in 1937 and was of material aid in reducing flood heights at and above Cairo.

At the latitude of Red River Landing, the project flood is estimated at 3,000,000 cfs. The project provides for dividing this great quantity of water, with 1,500,000 cfs of the flow continuing down the main river channel, the remaining 1,500,000 cfs being diverted to the Atchafalaya River via the Morganza and West Atchafalaya floodways, and the Old River Control structures.

Of the 1,500,000 cfs flowing down the main channel below Morganza Floodway, 250,000 cfs are to be diverted to Lake Pontchartrain and the Gulf through the Bonnet Carre' Spillway, located about 25 miles above New Orleans. The remaining 1,250,000 cfs will continue down the river to the Gulf.

That portion of the flow diverted from the main channel near Old River is carried by the Atchafalaya River, the Morganza Floodway, and the West Atchafalaya Floodway. The Morganza and the West Atchafalaya floodways follow down on opposite sides of the Atchafalaya River until the end of the levee system along the Atchafalaya River is reached; there they merge into a single broad floodway that passes the flow to the Gulf through two outlets, Wax Lake and Berwick Bay. In major floods, the Morganza would be the first of these two floodways to be used, with water entering it through a control structure just above Morganza.

Channel Improvement and Stabilization

Stabilization and protection of the riverbanks are important to the flood control and navigation plan, serving to protect flood control features and to insure the desired alignment of the river's navigation channel. This is accomplished by:

|

Cutoffs

|

Shortening the river and reduce flood heights. |

|

Revetment

|

Controlling the river's meandering. |

|

Dikes

|

Directing the flow. |

|

Improvement Dredging

|

Realigning the channel. |

Principal Tributary Basin Improvements

The Flood Control Act of 1928 authorized work that would give the various basins protection against Mississippi River floods only, although the tributary streams within the basins caused frequent flood damage that could not be prevented by the main stem Mississippi River protective works. Later amendments to this act have authorized work that provides alleviation of the tributary flood problems.

There are four major drainage basins in the lower Mississippi River Valley Project: St. Francis in east Arkansas; Yazoo in northwestMississippi; Tensas in northeast Louisiana; and Atchafalaya in south Louisiana. There are five flood control reservoirs in the tributary basin improvement plan: Wappapello Lake in the St. Francis Basin, and four lakes -- Arkabutla, Sardis, Enid, and Grenada -- in the Yazoo Basin.

Old River Control One of the most important modifications to the project was made in 1954 when Congress authorized the feature for the control of flow at Old River to prevent the capture of the Mississippi by the Atchafalaya River.

The first two features completed were the low-sill and overbank structures, the former to pass low and medium flows from the Mississippi to the Atchafalaya River in a controlled manner, and the latter to pass flood flows to the Atchafalaya in conformance with the flood control plan. Inflow and outflow channels were constructed connecting the low-sill structure with the Mississippi and Red-Atchafalaya rivers. A third facility -- called the Auxillary Structure -- was placed in service late in 1986.

As the closure of Old River would cut off an important shallow-draft navigation artery, a navigation lock was constructed just south of the junction of the Old and Mississippi rivers. This navigation lock is one of the most modern in the nation's inland waterway system. Channels were dredged connecting the lock to the Mississippi and Old rivers, and this feature was opened to navigation in 1963.

Navigation

|

No river has played a greater part in the development and expansion of America than the Mississippi. In 1705 the first cargo was floated down the river from the Indian country around Wabash, now the states of Indiana and Ohio. This was a load of 15,000 bear and deer hides brought downstream for shipment to France.

Invention of the steamboat in the early nineteenth century brought about a revolution in river commerce. The first steamboat to travel the Mississippi was the "New Orleans."

The Mississippi River is the main stem of a network of inland navigable waterways which form a system of about 12,350 miles in length, not including the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway of 1,173 miles.

Waterborne commerce on the Mississippi rose from 30 million tons in 1940 to almost 400 million in 1984. This heavy commercial traffic includes grains, coal and coke, petroleum products, sand and gravel, salt, sulphur and chemicals, and building materials among others. In addition, many pleasure craft from all parts of the country now use the Mississippi for vacation and travel.

|

|